IDENTIDADE

A CULTURA É AQUELO QUE CHAMAMOS NÓS

QUE É “GALICIA LATENTE”

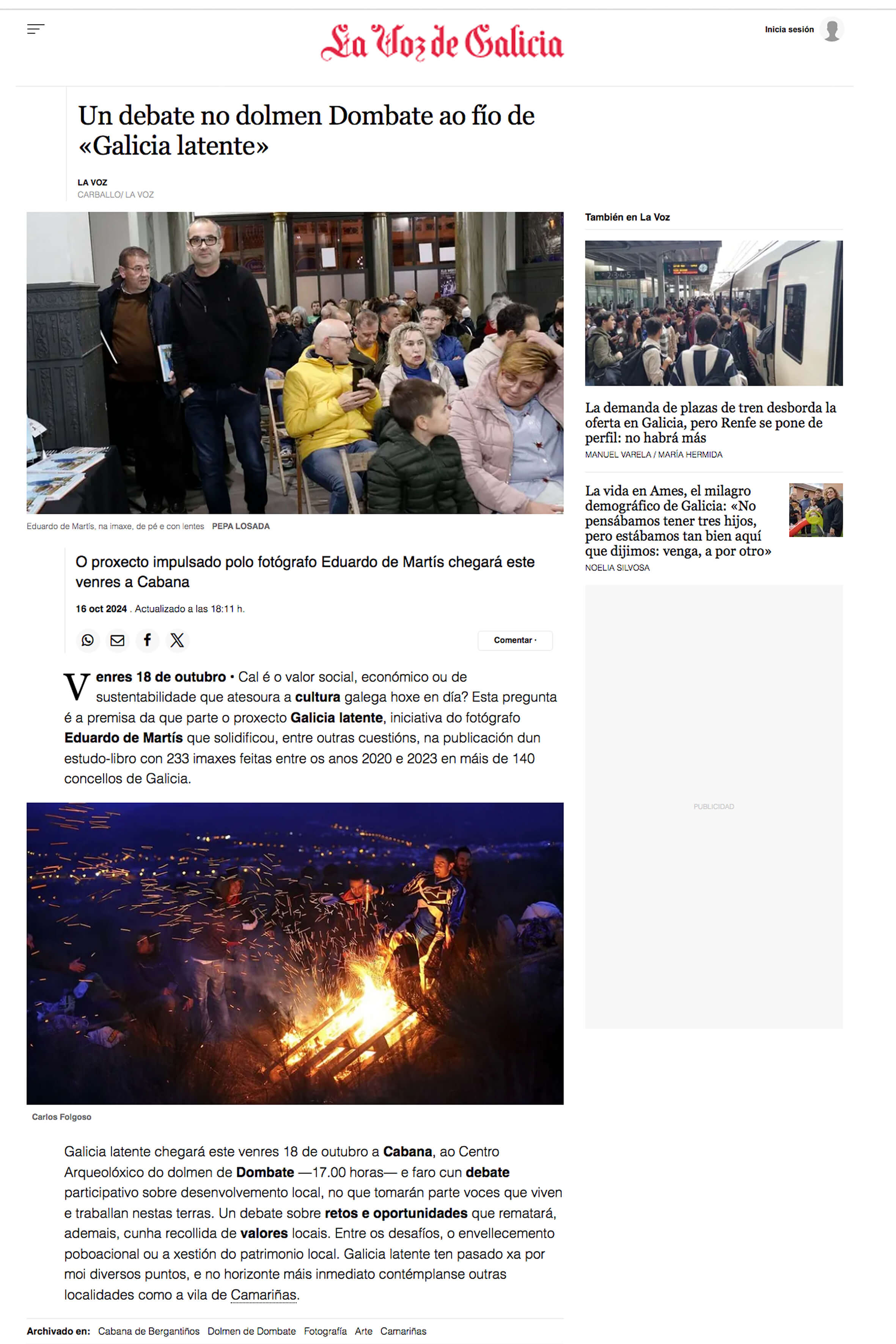

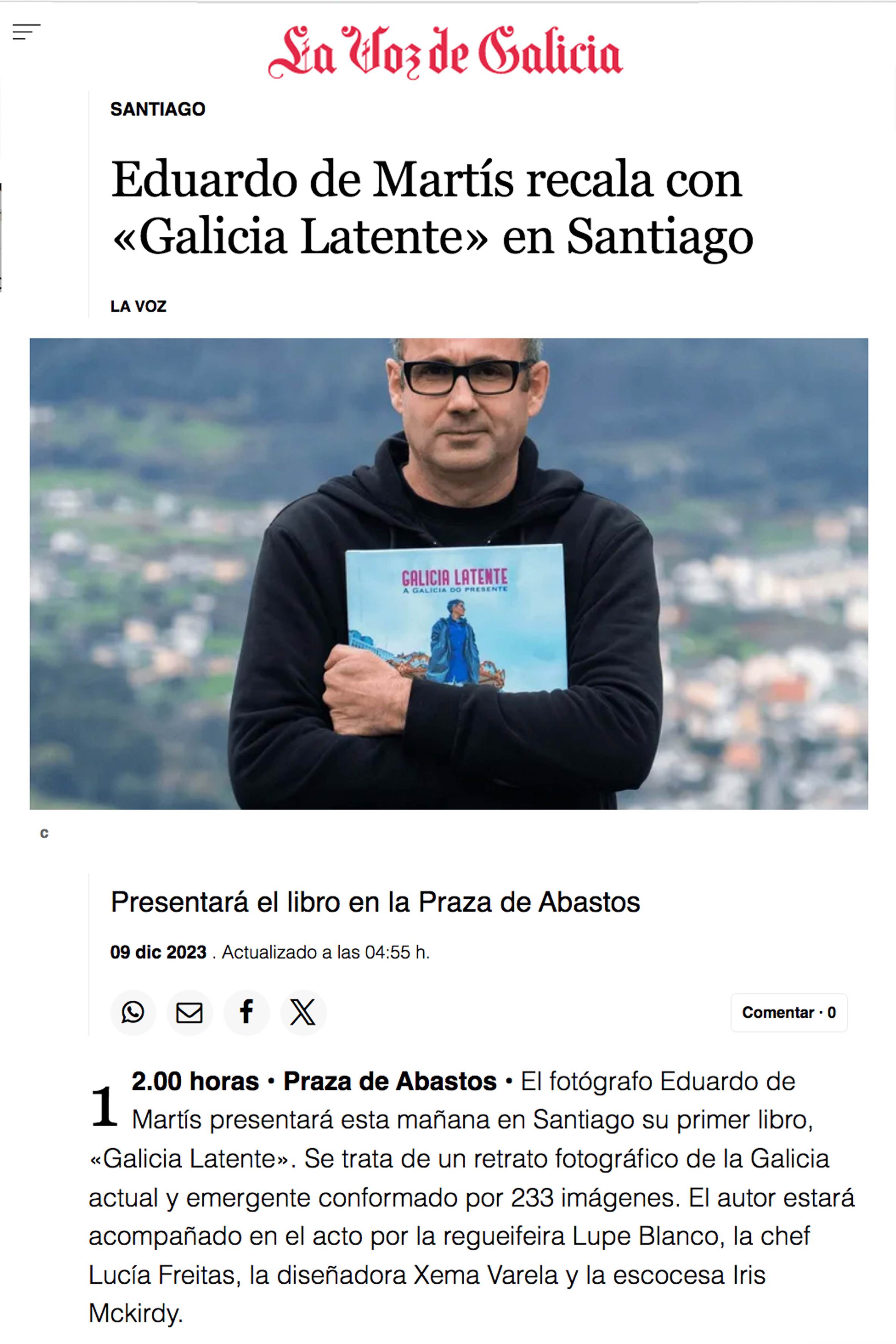

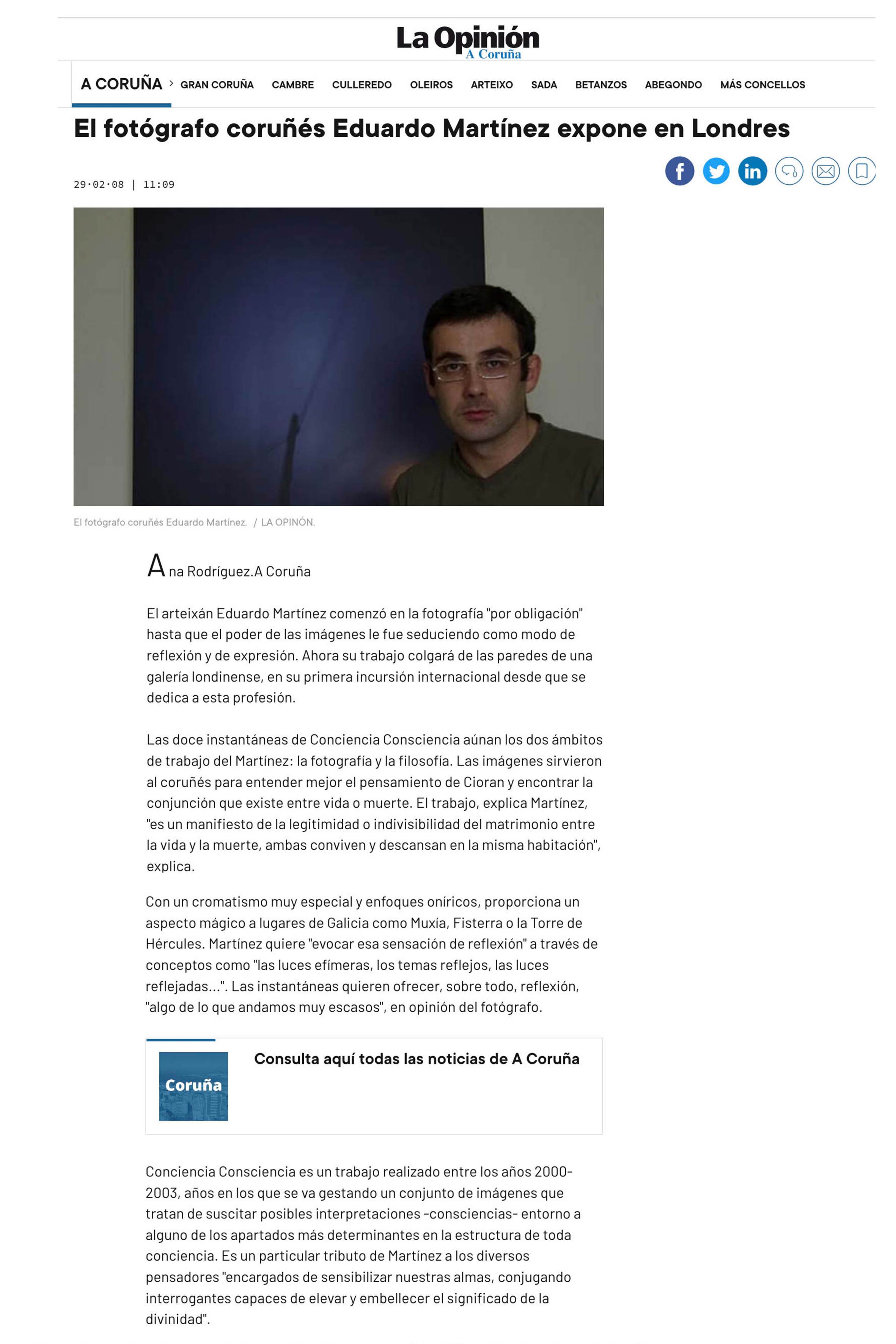

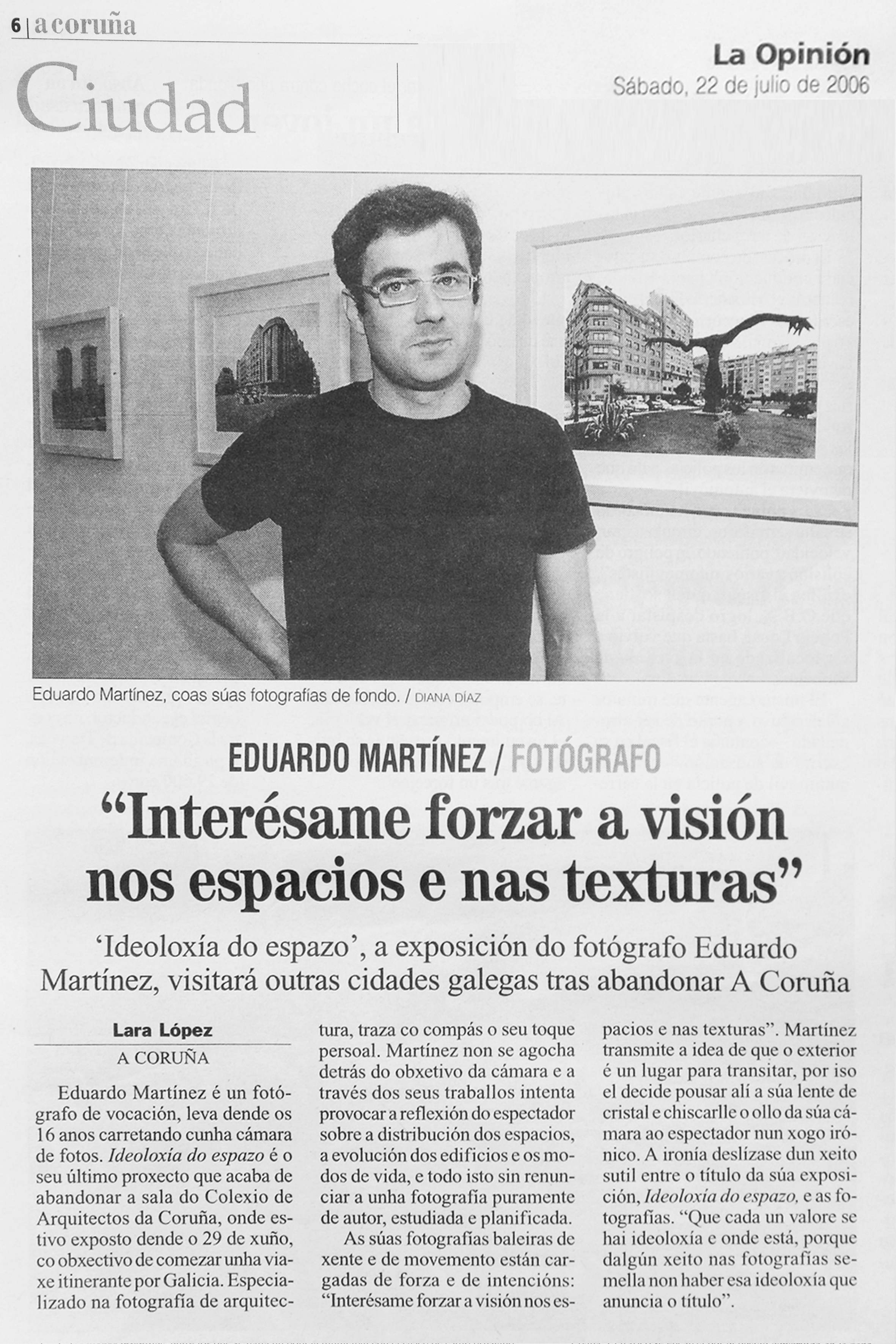

É un proxecto para a valorización da identidade cultural galega promovido por Eduardo de Martís, dende un marco de accións socioculturais.

“Galicia latente” é a única iniciativa do presente para desenvolver o potencial identitario da cultura galega. Promovemos accións participativas que nos conectan con realidades identitarias, de diversidades, de sostibilidade, rurais, de innovación ou interculturais. Unha publicación homónima feita entre os anos 2020 e 2023 ao longo de 146 concellos galegos dá conta das orixes do proxecto. Esta publicación reflicte diversas realidades do acontecer de Galicia. Xunto con outras iniciativas de dinamización, tentamos cubrir un baleiro sobre á identidade cultural galega contemporánea.

O proxecto céntrase en tres eixos principais. Aportar unha visión contemporánea da Galicia, achegala á sociedade e cooperar no alentar de porvires.

A NOSA MISIÓN

Promover os valores identitarios da cultura galega.

A QUEN VAI DIRIXIDO

Dirixímonos a persoas e entidades interesadas na valorización da identidade.

QUE APORTAMOS

- 1 O primeiro observatorio en liña, e axiña físico, da identidade cultural galega.

- 2 A primeira Fototeca da Galicia contemporánea, en liña.

- 3 Os I Premios das Identidades Culturais Galegas.

VALORES QUE NOS MOVEN

- 1 Achegar testemuñas innovadoras dos tempos e os territorios que nos conforman.

- 2 Fomentar a cooperación social e institucional.

- 3 Valorizar a identidade cultural como fonte de propósitos de vida.

- 4 Alentar as diversidades.

- 5 Tecer redes interculturais.

- 6 Potenciar as habilidades blandas.

A CULTURA É AQUELO QUE CHAMAMOS NÓS

COLABORACIÓNS DO PROXECTO

O proxecto Galicia Latente procura o valor da identidade cultural galega contemporánea. En consecuencia abrimos a colaboración a aquelas entidades e persoas que queiran participar neste latexar de Galicia.

Entidades que están a participar coa Galicia latente:

ORGANIZA:

GALICIA LATENTE

PATROCINA:

COFINANCIA:

COLABORACIÓN INSTITUCIONAL:

ENTIDADES COLABORADORAS:

ENTIDADES DE APOIO:

Texts in english from the “Galicia latente” book

PROLOGUE

The present work is a look into Galicia, the real Galicia, the tangible and visible, but also the subtle and invisible, the latent. The texts that come along this visual story are an attempt to contextualize and put into words the subtexts that the images hide, but they are also my particular vision of the personal perspective that Eduardo Martís offers of Galicia through his images. So the book you have in your hands is the communion of two ways of looking at our world: one of a photographer and one of an anthropologist, one through the image and the otherthrough words, with the aim that both perspectives intersect and complement each other tobuild another, more global, refined, and holistic view of our social and cultural reality as a country and as folk.

To talk about Galicia in a hundred images or in a few dozen pages is like trying to fit the ocean into a glass. But the water that fits in that glass will undoubtedly be part of the ocean, just as the photographs and words in this book are part of what we are or what we feel we are. The need to explain that immensity in a few words and to organize in my mind all those images and ideas that suggest us led me to create a series of analytical categories to shape such an endeavor.

We could use many others, or even none, but this was my way of approaching that analysis of what Galicia is today and trying to define some of the most significant elements of what builds its identity. That’s why we wanted to talk about the territory, the physical and natural place where this people settle and live; the landscape, as our particular vision and cultural construction of that territory; the culture, which makes us be and see the world as we see it; the identity that defines us and with which we identify; the society that is the framework we build to live in community; the economy and our ways of subsisting; and finally, our way of expressing ourselves through

language, the vehicle of our culture. These are the threads with which we weave this narrative, and these are the threads that served us to knit together this rosary of powerful images that speak to us and place us before the mirror of our own reality as a people.

LATENT GALICIA

Galicia treasures a rich historical, archaeological, ethnographic, and artistic legacy of incalculable value and a valuable natural heritage culturally constructed and interpreted over thecenturies. The Galician people are guardians and keepers of a cultural legacy and a tradition passed down from generation to generation that has shaped what we are today: our identity, ourculture, and our society.

Galician culture, like any culture, is not a fossil; it is not something immutable but dynamic, in constant change. What we are today is not the same as what we were yesterday, nor will we be the same tomorrow; but there is an Ariadne’s thread that connects past, present, and future, which makes us recognize ourselves as a distinct human group with our own identity despite internal diversity and the passage of time.

Our country also enjoys a privileged geolocation at the epicenter of the Atlantic world, a geographical and historical enclave of communication and cultural exchange between the Mediterranean and Atlantic Europe, but also between the old continent and America, and even Africa. We were the ‘end of the world’ of the Mediterranean, but also the center of the Atlantic world. Everything is relative; everything depends on the eyes that see. We know this well in Galicia. Additionally, it has a clear spatial identity that distinguishes it geographically from the rest of the Iberian Peninsula and Atlantic Europe.

Despite this individuality and unity from an external point of view, internally it has great diversity, reflected in the different ways of organizing spaces, land ownership, family structures, customs and traditions, linguistic variations, ways of subsistence, landscapes, resources, and even climates.

Seen as a whole, Galician culture is a minority culture in the sense that it is the culture of a small human group. But it is also a marginalized culture, having undergone a process of marginalization, persecution, or even prohibition at some point in its history. Therefore, our culture has suffered, and still suffers, from coercive actions that produce an acculturative impactand limit its forms of expression and development. In the face of this coercive power or force, different cultures and peoples can react in three possible ways: by resisting, resigning, or adapting. Resistance is the force that opposes the action of this acculturative force; resignation is the voluntary surrender of one culture or people, placing itself in the hands and will of another people or culture. The third way to face changes is resilience, which is the ability of our community to adapt in the face of a disruptive agent, a State, or an adverse situation. Galician culture and our people, consciously or unconsciously, have resorted to these three solutions at different historical moments. Periods of struggle and resistance have alternated with phases of diffuse resistance or submission and self- denial. But there is no doubt that the capacity for resilience, adaptation, and change has also made possible the continuity of our culture and even our language. It has also facilitated processes of hybridization, such as playing a rumbaon the bagpipes or eating corn pie today. Depending on each of these options, the consequences and transformations that our culture and society will undergo in their process of encounter or clash with other cultures, systems, or ideologies with which they interact will vary accordingly.

But Galician culture, in this global and interconnected world, also has immense potential for impact and expansion. Alongside the processes of cultural homogenization, there are also dynamics of empowerment and creative resistance, enabling Galician proposals, ideas, products, and creators to increasingly find a place in the global market. In this market, they not only offer their products and services but also spread seeds of Galician identity and distinctiveness. In this way, the world is enriched by the contribution of Galician culture, just as we can be enriched by the contributions that other cultures can make to us, as long as this exchange is conducted based on the principles of intercultural respect and equality of power. Therefore, there exists a latent and resilient Galician culture ready to burst into the world and occupy the space it deserves. It is important to reflect on the significance of cultural empowerment processes.

Therefore, it isof utmost importance that, in the face of capitalist globalization and the processes of colonialismand cultural destruction, vulnerable cultures around the world, such as the Galician case, foster what anthropology calls empowerment processes. These are understood as the processes through which the spiritual, ideological, political, social, economic, and cultural strength of a particular community can be increased to promote positive changes in their living conditions. Empowerment dynamics lead to an increase in self-confidence in their own abilities, an enhancement of self-esteem, and a deeper understanding of their own identity within peoples, cultures, and societies.

Creativity is a particular trait of Galicia, especially in the world of arts and literature, but also in other fields where survival has sharpened our ingenuity and creative and innovative spirit. So much so that we were able to create a universal game like foosball, to give a simple, fun, and

curious example. This creativity applied to the economy with the perspective of empowerment has led, in recent years, to the emergence in Galicia of companies and initiatives that work to valorize aspects of our culture, knowledge, and identity. It has also given rise to social and cultural movements and new processes of resource self-management more in line with the times and social needs, such as cooperatives, social economy enterprises, or communal lands, many of which are pioneers in the sustainable management of forests and their resources.

The control of one’s resources—be they material, symbolic, ideological, or, ultimately, cultural— leads to the reduction of vulnerability and dependence and significantly helps to diminish the subordinate position of a culture compared to others. Empowerment processes are essential to maintain the cultural identity of a people and to keep their culture in that constant flow so necessary for their survival. They are, above all, a challenge for vulnerable cultures like ours. Drawing inspiration and creativity from our own language, symbols of Galician identity— whether original or stereotyped—customs and traditions, beliefs, local knowledge, traditional music, mythology, or our particular way of being in the world or expressing ourselves is clearly choosing to value our culture and identity. Therefore, the implementation of these empowerment processes is very important to achieve an ideological and social transformation that allows us to stop being a subordinate culture dependent on external symbolic and ideological references, and to become conscious and proud protagonists and builders of our own history and cultural reality.

But for these phenomena to occur, it is essential to have self-knowledge, knowledge of our own culture, the type of society we have, our history, and our potential as a people. And for that, it is necessary to learn to analyze ourselves, to look at ourselves in different ways, moving away from stereotypes and established frameworks, looking at ourselves from both outside and inside.

That’s what we aim to do with this book: to learn to reflect on ourselves through our own perspective on who we are, who we were, and what we want to be, but also on what we appear to be and what escapes the eye. Learning to see the latent Galicia that surrounds us.

1. THE TERRITORY

Galicia, that Atlantic figurehead of the Iberian Peninsula, is a microcosm in itself, a rich and diverse space from a cultural, economic, social, and landscape perspective. With a geographic extension of 29,434 km2, it is larger than countries such as Israel, Albania, El Salvador, Slovenia, Equatorial Guinea, Rwanda, Kuwait, and fifty more nations. So, despite what one might think at first glance, Galicia is a relatively large and diverse country, characterized by an irregular and rugged relief where mountain ranges, mountains, and valleys alternate, a vertically and horizontally oriented country, enclosed between hills and mountains and, at the same time, open to the immensity of the sea. A land irrigated by thousands of rivers and with a coastline of nearly 1,200 kilometers stretching from the mouth of the Miño River to that of the Eo River. Geologically, 46% of Galician territory is composed of slate and another 45% of granite.

GEOGRAPHY

The morphology of the coast is varied, alternating between rocky areas formed by cliffs, headlands, capes, and rocks and sandy areas of beaches (750 sandy areas), coves, dune areas, bars, estuaries, and marshes. The rocky coast is the most common type of Galician coastline, and in the Capelada mountain range, the cliffs reach an impressive height of 600 meters. The shape of the coast is a consequence of the interaction and movement of water over coastal materials, and its continental shelf is narrow, reaching only 15 miles at its widest point. In the orography and coastal landscape of Galicia, the estuaries stand out, which we classify as high estuaries (Ribadeo, Foz, Ortigueira, and Cedeira), middle estuaries (Ferrol, Betanzos, A Coruña, Corme, and Camariñas), and low estuaries (Muros and Noia, Arousa, Pontevedra, and Vigo).

Galicia, despite its unity, has great physical and cultural diversity, with cultural and geographical contrasts in terms of landscapes and climates. Thus, we have a coastal Galicia of estuaries, coves, beaches, and cliffs, but also of densely populated and industrialized cities and towns. Additionally, we have an inland Galicia of plateaus, valleys, medium and low mountains, with an agrarian economy, with farms and large agricultural exploitations coexisting with traditional smallholdings and abundant pastureland and forestry operations. Let’s remember that in our territory, there are 11 million rural properties, and this endless smallholding coexists with the large estates that make up the communal lands. Finally, we have Galicia of high mountain areas, less populated, with limited agricultural land, and harsher climates.

This combination and diversity of climatic and environmental conditions mean that in Galicia, we find different areas with their own distinct characteristics, such as the northern and Atlantic coasts, the Rías Baixas, the central plateau, the northeastern mountains, the southeastern mountains, or the inland depressions and valleys. This morphology is the result of its geological constitution and the tectonic and environmental phenomena that have shaped it over millennia.

This tectonics is also responsible for the formation of the estuaries and the islands that protect them. The estuaries define our coastal landscape and have a privileged environment, both in terms of nature and socio-cultural aspects. They are also a sign of cultural identity and a natural economic and tourist resource. In the estuaries, there is a particular phenomenon of the merging of saltwater and seawater, which allows for the existence of one of the world’s most diverse marine ecosystems. Due to winds and marine currents (through an oceanographic phenomenon called upwelling, between spring and autumn), there is a significant increase in phytoplankton production, which serves as the main food source for many species and is primarily responsible

for their optimal growth. The presence of islands at the beginning of the estuaries, acting as a natural barrier, enhances the value of marine ecosystems.

OCCUPATION OF THE TERRITORY

The particular pattern of land occupation in Galicia, with its dispersion and abundance of small population centers, sometimes without a clear spatial break between them, makes it difficult to establish boundaries between purely urban and rural areas. Therefore, many intermediate settlements exist, not only physically but also ideologically, economically, and culturally.

Rural areas are considered those with low population density and without large urban centers (Leiro Lois et alii., 2006: 52). Typically, these areas have small towns that serve as the head of the region, generating economic and social dynamism. Rural settlements vary greatly in termsof morphology and functionality, and are characterized by their fragmentation and density of entities organized into hamlets, places, villages, or towns. Municipal administration was established in the first half of the 19th century but, along with the role of municipalities, the village, the parish, and the region continue to be the most important spatial and identity references for people.

The parish was in the rural Galician world the basic nucleus of territorial organization, the authentic social unit settled in a perfectly delimited, identified, and recognized territory by its residents. Although the parish has an ecclesiastical origin —the Code of Canon Law defines it as the basic unit of territorial delimitation of the Church, hierarchically grouped into archpriesthoods— over time, it took on a new meaning as the basic administrative unit to regulate community participation. The parish also has an economic and agricultural component,as it facilitates the organization of

traditional agricultural activity and the use of common resources, of which the communal forest is a good example. The term «parroquia» (parish) comes from the Latin «parochia» and the Greek «paroikía,» which means «habitation» or «assembly of inhabitants,» where «paroikos» means «neighbor» and «paroikein» means «to reside.» In an etymological sense, the parish comprises those who live together or inhabit neighboring areas.

Starting from the Cortes of Cádiz in 1812, the Old Regime fell, and a new liberal-style administration was implemented. These political, economic, and social changes led to the formation of modern municipalities, based on the parish as a reference point. The municipalities, in turn, are part of the regions, many of which correspond to the ancient Galician tribes mentioned in classical texts. Over the centuries, this peculiar Galician microcosm has witnessed many political, economic, and social changes, but for many Galicians, the parish continued to be their identity reference, their patria chica (hometown).

Since the 1950s, the traditional habitat has undergone profound changes, both in territorial and spatial distribution and in the appearance and typology of constructions. Let’s remember that the traditional Galician house was closely related to the specific characteristics of the physical environment in which it is located, both in terms of topography and climate, as well as the available construction resources. These changes in the way of inhabiting the territory also have an impact on the current Galician landscape.

Alongside this more rural reality, urban Galicia exists, with dynamic cities and towns constantly changing, each with a distinct identity. Some of them were already significant towns in medieval Galicia, such as Ourense, Pontevedra, Santiago, or Betanzos; others emerged strongly in the early

20th century due to industrialization, such as Vigo or Ferrol.

The development of the road network and infrastructure improvements make today’s Galicia no longer that imaginary isolated territory from the world. And I say «imaginary» because our country has always been open to the sea, and the sea has been and continues to be the great communication highway with the world. The development of road and transport infrastructure is fundamental for economic development as it facilitates the movement of goods and raw materials, access to workplaces, and the movement of people.

CLIMATE

Galicia has a climate with different local variations that generate various microclimates caused by altitude, orientation, the presence of the sea, etc. Galicia is one of the areas in Europe with the highest rainfall. The average annual temperature is 13.3 ºC, with an average in winter of 8.5 ºC and in summer of 19 ºC (in spring, 15 ºC on average; and in autumn, 11 ºC). The sea, like somany things in Galicia, also determines the Galician climate because its temperate and humid winds moderate temperatures and push the masses of clouds that produce rain. It is also responsible for the circulation of local breezes between day and night produced by the temperature difference between the air masses over the sea and those over the land. The Atlantic waters moderate temperatures: in winter, the warm waters of the Gulf Stream warm the air and make the climate more temperate, and in summer, the upwelling of colder deep waters lowers the temperature, making the climate cooler.

2. ECONOMY AND RESOURCES

In Galicia, there is a particular symbiosis between products and landscape. This close relationship between landscape and production is reflected in specific cultural aspects such as, for example, the diet, and gave rise to the concept of the Atlantic diet, centered on Galician and northern Portuguese gastronomy, also extending to Asturias, Cantabria, and the Basque Country. Galicia is a deeply humanized territory. There is probably no corner of the country that has not suffered, throughout our history, the action of human hands. Therefore, we do not have virgin territories; the entire country bears the human footprint, shaping a fantastic landscape culturally constructed over millennia. Thus, we have meadows and pastures, farmland, vineyards, and forested lands. Studies on Galicia’s productive surface reflect that it can be divided into almost three equal parts, depending on whether they are devoted to croplands, tree-covered areas, or shrub formations or pastures. Agricultural landscapes are the result of transformations produced by agricultural activity in natural spaces. They are the result of the combination of human activity and the physical and environmental factors mentioned above. These factors give rise to diverse landscapes such as open fields and enclosed fields, smallholdings, large estates, forested areas, livestock farming areas, terraced landscapes for vine cultivation, etc. The Galician landscape is associated with Atlantic forests, grasslands with significant livestock farming, dairy and meat industries, and, of course, the coast, from where large quantities of fish, shellfish, and other marine resources are extracted.

PRODUCTIVE SECTORS

Galicia boasts significant natural resources exploited since antiquity, such as various minerals. It has a productive sea that supports a significant fishing and shellfish industry. An agriculture

governed by the diversity of microclimates, leading to a rich livestock sector, diverse crops, significant horticultural activity, extensive cereal cultivation, and important wine-producing regions, which form the basis of intense economic activity. Agriculture continues to be an important sector of the Galician economy, employing a large number of people in agriculture, livestock farming, and forestry, alongside marketing and processing activities that contribute to this sector. Forage crops for livestock occupy the largest area, including potatoes, corn, turnips, beans, vegetables, various fruits, and grapes, which generate significant activity in the wine subsector.

Equally important is the artisanal sector, encompassing pottery, textiles, jewelry, and musical instrument construction. The cultural sector is dynamic, with literature, music, cultural creation, and performing arts, among others, shaping a growing sector with great potential for wealth and employment generation, currently accounting for 3% of the Galician GDP and 3.2% of employment.

The services sector, with tourism and hospitality as significant drivers, along with administrative, scientific, and technical activities, is the most important sector of the Galician economy and one of the fastest-growing in recent years.

Finally, the industrial sector (including automobile, chemical, and textile industries, among others), concentrated in cities like Vigo or A Coruña, and formerly in Ferrol, completes the industrial economic fabric of the country. Within this sector, the automotive industry is crucial forthe Galician economy, accounting for 14% of its GDP and representing 29% of the total exports of the region.

Galicia does not possess significant reserves of energy resources such as oil, natural gas, or coal.

However, due to its geographical location and topography, it does have great potential for harnessing renewable energies from wind, water, and solar sources. In recent decades, it has become a powerhouse in wind and hydroelectric energy production, although these benefits have not always been fully transmitted to its population.

The social and economic changes that have occurred in the last decades of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st, including the tourism boom, the tertiarization of the economy, or the limitation of overexploitation of marine resources, have translated into an intense process of transformation of the pre-existing social, economic, and territorial structures in Galicia. This transformation has been driven by Spain’s integration into Western capitalist economic circles, favoring industrialization and urban development in the national territory. As a result, there has been a new modification of the landscape, characterized by increased population density along the coast and tourism (especially seasonal), as well as an aging population and population decline in the interior of Galicia, particularly in the provinces of Lugo and Ourense.

MONTE COMUNAL (COMMUNAL MOUNTAIN)

An important and omnipresent element in the history, landscape construction, identity, and economy of Galicia is the communal mountain. The residents of Galician parishes have had, since time immemorial, and as a customary practice, collective ownership of the communal mountain. A mountain identified with their parish entity, and which has been, since the Middle Ages, a source of livelihood, being utilized by residents for livestock grazing, gathering of fodderfor fertilizing the land, timber harvesting, firewood collection, stone extraction, and for the use of springs and streams that emerge in the mountains for domestic consumption and irrigation of plots. The

mountain is also a mythical and symbolic universe around which, over hundreds of years, stories, tales, and legends have been woven by generations of neighbors who inhabited, worked, and traversed those mountain lands. These communal mountains, the basis of livelihood for many families and a fundamental complement to the Galician agrarian economy, underwent a process of usurpation from the 19th century onwards, resulting in the deprivation oftheir property and their legitimate uses to their rightful owners: the communal neighbors. This misappropriation and its subsequent illegal sale or alienation are currently causing many legal proceedings between mountain communities and municipalities and administrations for the recovery of their rightful property or, at the very least, for the payment of the compensation due to them for being deprived of their property and its exploitation. In parallel with this process of recovery and valorization of many communal mountains, with pioneering examples of sustainable management of their resources, there is also, especially in the older and more depopulated interior, the abandonment of many forest lands due to lack of generational turnover and settled population in the territory that can take charge and manage the communal mountains themselves. This is undoubtedly one of the great challenges for the future: how to preserve the self-managed and democratic management of communal mountains and how to make them profitable and ecologically sustainable in the face of the pressures and speculative interests of many large companies that see the abandoned mountains as a new source of wealth.

3. LANDSCAPE

Landscape is a way of looking at the natural surroundings. It’s a worldview paradoxically not so much because it’s the result of the exercise of the sense of sight but of assuming a way of thinking about the world. Honorio Velasco (2007) says that, in part, in Europe, the landscape isa discovery from contemplating the countryside from the city with the assumption (debatable) that peasants not only do not contemplate the landscape but become integrated subjects in it. The city dwellers’ view of the landscape is different from that of people from the countryside,who live immersed in what, for urbanites, is or should be a certain type of landscape. There’s a particular version of the elite in Western culture regarding landscape imagination, the rhetoric of pictorial compositions, views, and panoramas, tinged with a bundle of assumptions and aesthetic implications (Green, 1995). These attachments can prevent appreciating other multiple aspects of the landscape in Western societies. This is very palpable in the political and touristic construction of the Galician landscape. A «bucolic and pastoral» vision of green meadows dotted with stone cottages and picturesque granaries, and a rural area marked by winding paths adorned with wayside crosses where cows graze contentedly to the sound of bagpipes and tambourines played by locals at their gatherings and get-togethers. But the reality of our landscape is not that of tourist postcards or Tourism brochures, or at least not exclusively that stereotyped image that tourists and lovers of rural getaways for the weekend aspire toknow.

Landscape was already a cultural product in antiquity, and its cultures that provide ways of seeing things and ways of creating spaces. In different human societies and at different times, landscapes are multiple and loaded with multiple values, attached to an endless array of ideas and beliefs and,

therefore, contemplated or, better, experienced in very different ways (Honorio Velasco, 2007).

Galician cultural heritage also serves as a way to articulate and interpret the territory from a symbolic and mythical, but also social and political, perspective. Therefore, heritage is a catalyst for cultural ideology of the first magnitude. Around our heritage, the people have been constructing over time a popular discourse that reflects part of their worldview. As Malinowski said when speaking about Melanesian societies, «the mythical world receives its substance fromthe rock and the hill, from the changes in the land and the sea… one notices the vivifying influence of myth on the landscape.» Myths reveal a strong identification of people with the land and its landscape. Ancestors leave their mark on the landscape, the sacred, the healing place, the encounter with the extraordinary… That’s why Galicia is full of sanctuaries, crossroadswhere the Compaña appears, paths frequented by spirits, healing rocks, holy springs, mythical geographies, sacred mountains, Moorish threshing floors, houses of the Moor, old chests, witches’ meadows, serpent caves… The landscape evokes and refers to a past time but also renews and updates the worldview.

We can understand even the Galician landscape as a game of oppositions: between culture and nature, between the living and the dead, between us and them, between men and women, between the profane and the sacred, or between rural and urban. As Enrique Couceiro (2008) says regarding the landscape of the Miño region, «the worldview and cultural ethos of the Miño regions exhort that to be Christian and a contemporary man, one must also experience oneself as Moorish and ancient; to be mortal, one must catch a glimpse of holiness, carrying it with them; to be ‘us’, one must merge with ‘them’. And to descend and be a village, undoubtedly, onemust ascend the mountain and survey the landscape.»

There are also hidden landscapes in our geography. It’s not just what is seen but also what it hides and reveals: the existence of other worlds, of other hidden topographies, present in cultural landscapes and in the order of the world (Moorish tunnels, an underground world inhabited by mythical beings, sunken cities that appear on the night of San Juan, lakes that hideaccess to the Beyond, islands on the horizon where the souls of the dead migrate…).

One of the ways we culturally construct the landscape is by fixing the sacred in place. The landscape is structured by paths that go from one place to another but also connect the world of the everyday with the world of the exceptional. Paths that pilgrims take to sanctuaries. The pilgrimage shows how the path is a cultural construction of space by providing orientation, by configuring it according to a direction. Stages that can be determined by pre-existing enclaves, but the path generates and configures the stages by creating enclaves, and in both cases, it orients and redefines them. Galicia is itself an end of the road, and through it passes the first cultural itinerary declared by UNESCO: the Camino de Santiago. One wouldn’t understand whatGalicia is today and what it was in the past without this idea of the goal, the end of the known land, of the path and its symbolic meaning as a rite of passage and regeneration.

Our landscape also evokes morality. Sometimes, the landscape serves to provide guidelines for what is considered socially appropriate or inappropriate behavior. Understanding the cultural use of the landscape allows us to appreciate the process by which events from the past are recorded and made permanent, and how the concepts of time and temporal continuity, in part, are perceived and expressed in terms of place. These ideas saturate the Galician landscape with values and meanings, with which landscapes are seen and lived, translating into the planting of landmarks that operate as keys to personal and collective identities, linking the emotional with the

social and political, and constantly recharging the memory of the past to project it into the present. Places are built from memories. They evoke the memory of the people who inhabited them before and of the events that occurred. Sometimes we erect monuments whose explicit function is to bring some past time to the present, situating it in the center or on habitual routes, in the form of a relational and identifying space. Rites serve a similar function, they serve to «tie the times» in a continuity that is often fragile. Through the landscape, we travel through itineraries and places that hold memory and that we keep in memory, allowing us to recognize a territory and a space-time that is not foreign to us and on which part of our identity pivots. Part of our identity and existence depends on being there, in those landscapes.

A territory where different cultural elements from past times survive, inherited by generations and reinterpreted, restructured in a new dynamic and ever-changing cultural landscape. Presentsociety adapts to a socio-historically pre-adapted landscape. According to Fernández de Rota (1984), time is the vertebral dimension of cultural space. The festive calendar structures and orders the year, life, and consequently the landscape, creating temporal centers where people gather and socialize. This implies a spatialization of time in the delimitation of socio-spatial areas. It is a structuring of time supported by the ritualized use of space, which also serves to regulate social life.

The spatial map is constructed by accentuating the boundaries and highlighting within it a center capable of condensing multiple uses and meanings. The parish center as a cultural concentration and maximum social gathering; the communal mountain as the opposite extreme, less domesticated nature, a marginalized periphery less frequented; the intermediate zones shaped by waters, highly cultured and socialized nature (orchards, plots, agricultural spaces), and the paths

(cultural construction, social communication route integrated into the parish territory). In the landscape, there are structurally stable elements and others periodic or mobile, making certain spaces become centers of social life. Sometimes local and sometimes even extracommunitarian, as with parish festivals, pilgrimages, or fairs. It’s as if the territory were articulated into different centers that can be mobile, rotating, periodic, or circumstantial. Eventhe border can constitute a center. The Galician landscape is marked by boundaries in its structure through fences, walls, stone constructions, enclosures, trees, landmarks, and borders that are sacred. The orography of the Galician landscape is configured by centers, paths, and boundaries that are culturally constructed even though physical elements may exist. They are a symbolic language that speaks to people; they are a means of communication. The organization of space is based on the orography and reuses it for cultural purposes. The orography itself is the result of a long process of elaboration thanks to the physical effort and social interpretation of generations that inhabited that territory. An orography, as explained by Fernández de Rota (1984), on which material and mental forms are culturally constructed and that exists throughthe way of life of the current members of society; without them, the material construction collapses, and the cultural one does not exist.

The study of the landscape becomes a way to analyze the different forms of classifying, dividing, and identifying characteristics of each culture (parish, village, place, house, neighborhood…). The material components that make up the landscape become a set of meanings that can be read in different ways by cultural protagonists. The meaning of the different elements that constitute space is related to the other structurally interacting elements, combining in syntagmatic chains. Therefore, the landscape possesses a broad polysemy. Anthropologist Margaret Rodman points out that places—and even more so landscapes—are multivocal like symbols, in the sense that

they mean different things to different people or in different situations.

Enrique Couceiro states that the traditional landscape, primarily the mountainous landscape, was driven to treasure and express formulations about good and evil, about cosmogenesis, social hierarchies, values, virtues, and prototypical weaknesses of man; and it is also an expression of the archaic and decisive changes survived in the historical process from a local perspective. The people of the mountain villages managed to imagine—or see—from the lived experience of the sensory, of full participative bodily immersion, the surprising multidimensional change. I extend this assertion by Couceiro also to the people of the coast, who knew how to see in the sea and in its organic landscape those other visible and hidden landscapes.

Identities are also filled with references to the places that populations occupy. A space marker that each one carries from birth and that is even manifested in the name or nickname: I am so-and-so from such-and-such place, from such-and-such house, from parish X. One exists in relation to the group to which they belong and to the place to which they belong. Space-time marks with which to shape identities that societies select to appear different from others. Intangible heritage, with its uses, customs, knowledge, myths, rites, beliefs, and practices, was and is a fundamental tool for building the landscape. A Galician landscape looked at and seen through our culture, a landscape created through the worldview of a people.

4. SOCIETY

POPULATION

The Galician population is almost three million people (2,689,152 inhabitants in the year 2022, with a density higher than the national average) distributed unevenly throughout the territory, in an infinitely capillary network of population entities, to such an extent that Galicia concentrates 58.6% of all singular population entities in Spain, according to data from the National Institute of Statistics. Of these population entities, seven cities have more than 60,000 inhabitants (Vigo, A Coruña, Ourense, Lugo, Santiago, Pontevedra, and Ferrol) and together they concentrate almost one million residents. Another 49 towns with more than 10,000 inhabitants each aggregate another million people. In contrast, 200 of the 313 Galician municipalities have fewer than 5,000 residents. We have witnessed in recent decades a phenomenon of population concentration in increasingly larger urban and peri-urban areas. Administratively, Galicia is divided into four provinces and 313 municipalities.

Throughout the 20th century and into the 21st, the dynamics of population distribution have led to the existence of areas that have been growing (mainly the coastal regions) and others that have been losing population (the inland regions). Changes in the economic structure have caused a rapid process of urbanization and de-ruralization, with the consequent movement of populations and a decrease in the importance of the primary sector. Agricultural and livestock activity has declined, leading to an increase in the industrial sector and, in recent decades, the services sector, with a special emphasis on tourism and hospitality. All these factors have been decisive in this

migratory process towards the more populated, urban, and industrialized centers. This migratory process towards these urban centers causes Galicia to be the autonomous community in Spain with the most uninhabited population centers: of the 10,633 entities with no inhabitants registered by the National Institute of Statistics (INE), 3,954 are located in the four Galician provinces.

In terms of demographic aspects, Galicia faces an aging population problem and a great challenge for the future. Galicia’s population growth is marked by a low birth rate: 1.1 children per woman, below the necessary rate to ensure generational replacement. At the same time, it has one of the highest life expectancies in the world, lower on the coast than in the interior. Since the 1990s, there has been a stagnation in the demographic structure that is causing a serious aging process in the Galician population.

SOCIETY

Often, we hear part of Galician society being classified as a traditional society. When we talk about traditional society, we refer to a form of social group, a human organization based on traditional rules and values, on customs established in the past and transmitted from generation to generation. These are societies characterized by the importance of family and its kinship systems, where the sense of community prevails over individuality, where social roles are conventionally established and often marked by age, status, and gender of individuals. They aresocieties more resistant to change because tradition has marked and continues to mark their norms of behavior and their worldview. In these types of societies, religion plays a significant role in establishing ethical and moral codes for its members. Regarding the economic system, they tend to be agrarian societies with subsistence economies.

It is undeniable that the Galician people, like many other European peoples, retain in their culture and social organization, especially in rural areas, important traces of the ideological universe of the so-called traditional agrarian societies. But we cannot say today that Galician society is a traditional or immobilized society. In fact, contemporary Galician society is diverse and complex, where urban and rural worlds coexist but also the urbanized rural world and the urbanized rural world, creating interesting interfaces and border spaces like the so-called rurban, a hybridization of both worlds.

SOCIALIZATION

The personality of individuals does not develop in isolation but within cultural environments and contexts. Socialization is the process by which human beings learn, throughout their lives, the sociocultural elements of their environment and integrate them into the structure of their personality under the influence of experiences and social agents. In socialization, a person internalizes their culture from a particular society. It is the process by which culture is instilled in the members of society; through it, culture is transmitted from generation to generation, individuals learn specific knowledge, develop their potentialities and necessary skills for adequate participation in social life, and adapt to the characteristic forms of organized behavior of their society.

Socialization is possible thanks to social agents, which can be family, school, peers, or the media, among others. Social agents are representative institutions and individuals with the capacity to transmit and impose appropriate cultural elements. The most representative social agents are the family, fundamental because it is the first social level we have access to, and theschool as a transmitter of knowledge and values. Socialization agents have been changing in Galicia, and

currently, the main ones are family, school, media and social networks, and peer groups. The role of the Church, fairs (replaced by shopping centers), or the army, in the case of young people, has declined. However, patron saint festivals, pilgrimages, or folk festivals, whichare returning stronger than ever, continue to be notable spaces for socialization and one of the significant traits of our culture. We must not forget that these types of rituals are social acts in which some participants are more committed than others to the beliefs underlying the rites (for example, in pilgrimages), but the mere fact of participating in a collective public act indicates that the participants accept a common social and moral order, one that transcends their status as individuals, temporarily immersing their individuality in a community.

The extended family still has an important weight and role, although in cities the nuclear or single- parent family predominates. The network of friendships and the community, especially in rural areas, play a relevant role in social organization.

Another important cultural factor in Galicia is the rites of communal eating. Galicians love to eat and eat together. It is a stereotype but also a verifiable cultural reality due to the number of gastronomic festivals held throughout the year and the various gatherings, meals, and banquets we attend throughout our lives. Celebrations linked to the ritual festive cycle of the year (All Saints’ Day, chestnut festivals, Christmas, Carnival, Saint John’s Day…), patron saint festivals, significant moments in the life cycle (births and baptisms, communions, weddings, sacraments, etc.), communal work, or any important celebration is accompanied by a banquet where theidea of a mesa farta (bountiful table) always prevails.

Eating is more than just nourishment. Beyond its biological function for human subsistence, it is a cultural act and an act of identity reaffirmation. Eating is exalting life: the dead do not eat, the living do. Banquets and feasts are also a way of marking status and rank: those who provide food are those who have the most, those who can gain loyalties and followers. Social prestige isalso seen in the banquets that are held, as it is a way of showing the strength of the household and the possibilities of those who can eat what others cannot. Eating together is a way of honoring those who are not present or those who are to be honored. Furthermore, these rites of communal eating have a socializing function, fostering solidarity through the distribution and exchange of goods, they are community-building events (both of the neighborhood and of kinship). They are also important economic stimulators and a negotiating tool, as the utilitarian nature of certain exceptional banquets is evident, where the aim is to obtain a certain capital of social relations or to show the need to offer something in return for the services received. Finally, these communal banquets are a moment of collective joy, of life, and of provocation andpassion against the fasting, abstinence (formerly enforced by the Church), and self-control that society imposes.

5. CULTURAL HERITAGE

We define cultural heritage as «the cultural inheritance from the past of a community, maintained to the present day and transmitted to present and future generations.»

When one speaks or thinks of Galicia, it is inevitable not to recognize its wealth of heritage. An archaeological legacy dating back to the Paleolithic: seven thousand megaliths, nearly two thousand rock art sites, about five thousand Iron Age hillforts, the world’s only functioning Roman lighthouse, the only Roman wall that retains its entire perimeter intact, one of the finest examples of Romanesque architecture in Europe, castles, monasteries, manor houses, churches, chapels, cathedrals, thousands of ethnographic assets (mills, wayside crosses, granaries, fountains, bridges…), and one of the three holy cities of Christianity are just some examples of this incalculable cultural heritage. But if the material heritage is abundant, Galician intangible heritage is immeasurable and fundamental to understanding our culture and identity. Our language, rich mythology, traditional music, oral literature, ancestral knowledge, popular religiosity and its forms and expressions, ethnomedicine, festive celebrations of the annual cycle, etc., are defining elements of our heritage and identity as a people. As for natural heritage, the orographic and ecosystem diversity generates a natural wealth that, beyond its scenic or ecological value, has been and continues to be the source of subsistence and resources for the societies settled in this territory since prehistory. Hence the importance of the Galician estuaries for fishing or the value of communal mountain land in agriculture, livestock farming, or forestry. A wealth that has not always been considered and valued as such, but that has always been there, present in the landscape and in the collective imagination.

In recent decades, the issue of cultural and natural heritage, and its valorization, has gained weight and importance in society. Its role in shaping our identity, its cultural and even tourist andeconomic potential, are aspects present in the current debate about what heritage is and what to do with it nowadays. That’s why the Convention concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage (UNESCO, November 16, 1972) aims to promote the identification, protection, and preservation of cultural and natural heritage considered especially valuable for humanity. And Galicia is not exempt from this debate.

The concept of cultural heritage is subjective and dynamic, not depending on objects or assets but on the values that society in general attributes to them at each moment in history, determining which assets are to be protected and preserved for posterity. It should be the Galician citizenship that defines at each moment in its history what heritage is for it and what is not. Therefore, the vision of what we consider heritage to be preserved has been changing over time. The overexploitation of natural resources, the destruction of archaeological sites, and valuable architectural, historical, ethnographic, or artistic assets to make way for amisunderstood progress have been the usual pattern in the last 150 years. In the late 19th century, for example, the medieval walls of many Galician cities were destroyed because they hindered the urban growth of the old towns and were seen as an obstacle to «progress.» Today, this would be a crime against heritage, but, on the contrary, we are destroying or letting valuableexamples of our industrial heritage fade away, when in many European countries they are already objects of conservation and valorization. So the concept of heritage should make us reflect on which elements of our history we want to preserve and on which elements we wantour identity and collective memory to pivot. The houses of the indianos (Galician emigrants who made their fortune in the Americas) that we now value and proudly display were once classified as examples of bad taste, nouveau

riche vulgarity, and constructions without artistic value. Perhaps in a few decades, we will look at the so-called feísmo (uglyism) with different eyes and discover in it a differential fact to study and, why not, to preserve.

When we talk about heritage, we usually differentiate between material, immaterial, and natural heritage, although the boundaries of these categories are sometimes elusive. Material cultural heritage would be the cultural legacy of the past of a community that possesses a special historical, artistic, architectural, urban, or archaeological interest. Intangible cultural heritage would consist of «the practices, representations, expressions, knowledge, and techniques—along with the instruments, objects, artifacts, and cultural spaces that are inherent to them—that communities, groups, and, in some cases, individuals recognize as an integral part of their cultural heritage.» By natural heritage, we understand the variety of landscapes that make up the flora and fauna of a territory. UNESCO defines it as those natural monuments, geological formations, places, and natural landscapes that have significant value from an aesthetic, scientific, and/or environmental point of view.

The value of heritage can be cultural or emotional, physical or intangible, historical or technical. In any case, heritage resources in Galicia are subject to utilization and are a driving force for cultural and economic development. Heritage, especially the intangible aspect, as a source of knowledge and practices, is a font of knowledge that can foster sustainable social and economic growth that strengthens the population in the territory and promotes local development.

THE INTANGIBLE HERITAGE AND CULTURE

Within the realm of heritage, intangible heritage holds fundamental importance as it is an essential component of a people’s culture, understanding culture as anthropology does, especially as a matter of ideas and values or as a symbolic system, as we have already explained. We find, then, the deep connection between heritage and culture.

On October 7, 2003, UNESCO adopted the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, understanding it as «the practices, representations, expressions, knowledge, and techniques—along with the instruments, objects, artifacts, and cultural spaces that are inherent to them—that communities, groups, and, in some cases, individuals recognize as an integral part of their cultural heritage.» We see, therefore, that Galicia’s intangible heritage encompasses the fundamental aspects that shape our Galician culture, namely, language, rituals, beliefs, knowledge, artistic creations, music, trades, or ways of seeing, ordering, and occupying our territory.

The Intangible Cultural Heritage, transmitted from generation to generation, is constantly recreated by communities and groups according to their environment, their interaction with nature, and their history, instilling in them a sense of identity and continuity and thus contributing to promoting respect for cultural diversity and human creativity. Therefore, it is also important to emphasize the relationship between intangible heritage, tangible heritage, and natural heritage.

UNESCO highlights the importance of intangible cultural heritage as a crucible of cultural diversity and as a guarantor of sustainable development, as well as the invaluable role it plays as a factor of bringing people together, fostering exchange, and promoting understanding among human

beings. The said international organization warns that processes of globalization and social transformation bring, along with phenomena of intolerance, serious risks of deterioration, disappearance, and destruction of intangible cultural heritage. That is why its safeguarding, maintenance, and recreation are urgently needed as a contribution to enriching cultural diversity and human creativity. Galicia’s intangible heritage is one of our great cultural riches as a people, and within it lie the keys to understanding our culture.

6. CULTURE

What is culture? And what is Galician culture? we wonder. The definition of culture is a subject of controversy and debate. In recent decades, the term has been used with multiple meanings (material culture, digital culture, work culture, business culture, cultural figures, etc.). Undoubtedly, the difficulty in defining the term arises because the concept of culture is used to label various states of consciousness that occur at different levels of abstraction.

Often, when we talk about culture and Galician culture, we immediately think of literature writtenin Galician, the arts, Galician music, fashion, and any other expression of what in anthropology we call expressive culture. But culture is much more than that, much more than art or what is shown in museums, exhibitions, and performances. Culture, and Galician culture, is, above all, something else. Culture is our particular way of seeing and being in the world. Culture, our culture, with its values, enables understanding and living together in a community. But it also allows us to understand our world, to order it, to express it. It is a tool for action and for observation and understanding.

In the 17th century, Samuel Pufendorf (1632-1694) defined culture as everything that is not a product of nature, but of human effort. This definition is too broad and diffuse to serve as a reference, although it already hinted at some important aspects, such as relating culture to human creation. Centuries later, Alfred Weber (1868-1958) related culture to the most creative aspects of the human spirit (myths, religious beliefs, etc.), as opposed to civilization, which would refer to the

more rational and technical aspects of society. This antagonistic definition against the concept of civilization already leads us more towards the symbolic world of the human being, the true foundation upon which culture transits. However, it was the classical definition of culture by the anthropologist Edward Burnett Tylor in 1871 that enjoyed greater validity, and even today some still rely on this definition despite it being surpassed many years ago. According to Tylor (Primitive Culture, 1871), culture is «a complex whole which includes knowledge, beliefs, arts, morals, laws, customs, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society.» In this definition, excessively broad, we see, nevertheless, thatculture is related to the way of thinking and acting of a community. Thus, generally, culture is understood as the more or less formalized way of thinking, acting, and feeling shared by a plurality of people, and which serves to constitute those people in a particular and distinct community.Therefore, summarizing and simplifying, we could say that culture is a shared mentalmold by a community, including norms, values, ideas, cognitive structures, beliefs, cosmologies,theologies, etc. These elements can be arranged in different ways, but are distributed among certain perfectly delineated societies. This is the case of Galician culture. Anthropologist Clifford Geertz was fundamental in the study of the concept of culture, as he established the inseparable connection between culture and symbol, defining culture as «a historically transmitted pattern of meanings embodied in symbols, a system of inherited conceptions expressed in symbolic forms by means of which men communicate, perpetuate, and develop their knowledge and attitudes toward life.»

Culture is, therefore, especially a matter of ideas and values. It’s a collective mental mold. It’s a symbolic system, as ideas and values, cosmology, morality, and aesthetics are expressed through symbols. We can define a symbol as something that represents or suggests a reality different from the visible or symbolized thing. The symbol refers to another non-present and invisible reality called

the «symbolized reality,» where the first serves as a mediation to the second. Symbols are of utmost importance in culture and the process of enculturation because people not only construct a symbolic world but also live in it, and symbols serve to enhance social cohesion; for example, religious symbols or collective rituals, which express and affirm the values of the group. We know this well in Galicia, which is why both devout believers and non-believers attend pilgrimages: they go seeking the divine intercession of the saint or the festival and communal eating around servings of empanada and octopus at the fair. Because participation in the ritual creates community beyond what each believes internally. Therefore, every community needs to define its collective symbols as those that maintain the sense of belonging and solidarity among the members of a group. In the construction of any human collectivity, whether it be a parish, a nation, a state, or a company, the creation of identity symbols is of utmost importance. That is to say, symbolic elements that allow that community to identify itself—and be identified—as participants in a common and distinctive «something» that sets them apart from other groups and defines and individualizes them against the foreign. The Galician people, like any community, need symbols that remind their members that they are partof the same group, that affirm them in their identity, and distinguish them from other collectivities. And that is the function, for example, of a flag, a coat of arms, or a national anthem, but they can also be, and are, Galician collective symbols such as a city like Santiago de Compostela; a type of food or diet, like seafood, fish, or the Atlantic diet; a musical instrument such as a bagpipe; and it can even be a collective symbol as subtle as a feeling: our longing (morriña).

Culture is not inherited biologically but intellectually. It’s not carried in the genes. Culture is, therefore, behavior according to certain models that each individual learns from birth and as they

are educated (socialized and enculturated) by their parents to become a member of the particular group in which they were born or to which they have joined. That’s why education in cultural values is so important and, among other aspects, the preservation of the native language. This means that a Galician person can be born anywhere and have the phenotype as long as they are enculturated in Galician culture. Similarly, being born in Galicia does not guarantee that one participates in Galician culture unless there is transmission of cultural valuesand symbols, and these are seen as one’s own. It is important to understand this to comprehend the sense of belonging and Galicianness of the diaspora and the children and grandchildren of emigration, but also to facilitate and understand the integration and Galicianization of many people born outside our geographical and cultural borders but who, living here or brought hereat a young age, decide to incorporate Galician culture as their own and, therefore, are Galician.

POPULAR RELIGIOSITY

Religious beliefs are one of the fundamental constitutive elements of a people’s culture. We can affirm that religious beliefs are an anthropological universal, a cultural universal even though nota human universal. That is to say, in all cultures we find beliefs that we can label as religious,but not all individuals within a culture hold religious beliefs. The study of the forms of popular religiosity adopted by members of each cultural community provides us with fundamental knowledge about the cultural and social forms adopted by each people, not only about their wayof ordering and interpreting the world and behaving in it, but also about their internal tensions, fears, needs, and desires.

The ideological systems that make up our spiritual or religious beliefs are cultural structures so

deeply rooted in societies that they tend to persist —at least many of their traits— for centuries, despite the changing times, peoples, and creeds. The rituals that accompany these beliefs, like the beliefs themselves, are fundamental for the cohesion of the social group, for the construction of cultural identity, and for maintaining the idea of unity and of culture collectively shared by a human group, to make us participants in that specific and individualized community and to differentiate ourselves, at the same time, from other social groups. Hence, this type of ideological structures endure over time, sometimes adapting, remodeling, or reinventing themselves to coexist with new religious ideological structures. The amalgamation and interweaving of beliefs, symbolic systems, and pre-Christian rituals within the ideological and practical framework of Galician Christianity or our popular religiosity is something obvious and undeniable, as is the antiquity of many of the beliefs that today coexist harmoniously with Christianity, to the point of being imperceptible to the common people. It is often recognized that the Christian religion and, specifically, Galician Christianity, inherited components from the Greco-Latin tradition and, obviously, from the Hebrew religion. But also from the Celtic tradition and even earlier ones. These customs and beliefs stemming from pre-Christian ideological substrates, these so-called «survivals» that we sometimes see in the ritual practices developed in Galician sanctuaries or in ethnomedicine, exist and persist because they continue to fulfill a purpose, they are not useless fossils. Therefore, Galicians do not repeat past customs like automatons without being aware of what they celebrate, but rather maintain rituals, myths, and beliefs because they are still relevant, because they still have functionality, or because theyhave been endowed with new meanings and utilities.

Just by observing the importance of sanctuaries, the cult of saints and the deceased, the rich protective and healing ritualistic practices that remain alive, beliefs in supernatural beings, or the

significance of the ritual festive cycle of the year, one can understand the role that popular religiosity plays in Galician culture. We could say, in a simplified way, that popular religiosity is the religious experience of the people, but it is necessary to clarify this concept further. As Ana Azor explains (2004: 15), popular religiosity refers to a series of varied and disparate religious manifestations, with an ambiguous definition, which in any case constitutes one of the most significant components of popular culture. According to Enrique Dussel, popular religiosity is «the fundamental nucleus of meaning of the totality of popular culture because it is where the practices framing the ultimate significance of existence are found» (1988:14). Galician popular religiosity also shows a resistance power of these popular practices against the impositions of the official religion, while giving primacy to the direct relationships between human beings and the supernatural world. Therefore, popular religiosity and official religion, despite showing certain oppositions, coexist within our culture, share time and space, and often appear mixed to the point where it is difficult to distinguish where one frame of reference ends and the other begins.

7. IDENTITY

Culture, like heritage, is also closely linked to the concept of identity. Chaney said that culture is always a bridge between individuals and their identity. Identity is realized through participation in culture. The concepts of identity construction and culture are born together, says Zygmunt Bauman.

Galician cultural identity is the set of traits that allow us, as a group, to recognize ourselves as unique and different from others, which creates a sense of belonging. But the answer to the question of what these cultural traits are that allow us to identify ourselves as belonging to the same culture is complex and depends on the different perspectives from which the concept of identity is approached. In my opinion, there are a series of differential traits that we can call objective, such as language, but then there are other aspects that are less obvious and that shape our uniqueness, such as our particular relationship with death, our myths and rituals, the historical narrative of our past, or our particular sense of humor, defined as retranca (wit).

In our cultural world, eminently symbolic, deceased family members also coexist with the living in a relationship that transcends the temporal and earthly dimension. This coexistence and relationship is a symbiotic one, of mutual exchange that we can observe in multiple practices and beliefs related to the world of the deceased and souls, and that even leave their mark onthe landscape in the form of «petos de ánimas» (small stone structures) and wayside crosses.

And I say it is symbiotic because souls—just like saints—are asked for favors, but prayers are also offered for them, and a whole array of practices is set in motion that ultimately seeks tohelp these souls leave Purgatory and attain eternal peace.

Myth, so undervalued today but so important in Galician oral tradition and in the cultural configuration of its territory, structures our beliefs and our way of seeing the world. It explains our past and our world through a symbolic narrative. Jean-Pierre Vernant defined mythology as «a unified set that represents, through the extent of its field and its internal coherence, a system of thought.» Mythical narratives are a kind of containers that hold knowledge, beliefs, values, social, legal, or religious norms, explanations of natural or cultural reality. As Paul Bohannan explains (1986), myth provides both an explanation and a sketch of social relations and humanity’s relationship with the rest of nature. It provides moral and religious examples. Therefore, these types of stories that shape our oral literature, our view of the past, and our popular religiosity are often repositories of values, creeds, and religious practices. Myth conditions behavior and the interpretation of reality and, among other things, has served to organize and build the landscape and territory, as we will see.

Rituals are social, formalized, and symbolic mechanisms that help to cohesionate the social group and reaffirm its cultural identity, and moreover, they update and bring myths into the present. History is the narrative of our past, more or less close to reality, but in any case with a huge literary and political component.

History can be made by us or it can be generated exogenously to society and culture. Knowing one’s own history is knowing the origins, understanding where we come from in order to better

understand what we are and what we want to be. Nationalist movements have always used history and myth to build collective identities. Galician identity is closely linked to these romantic ideas of a heroic Celtic past and times inhabited by extraordinary races, kings, deities, and heroes. Our own Galician anthem is an ode to these ideas. But also to the Jacobean myth, to Christianity, and to regenerative power, whether of the sea, pilgrimage, or the Holy Grail that illuminates our flag. Retranca is a way of speaking and behaving that is defined by caution, the ability to answer evasively, to avoid saying or doing what others want us to do. As Marcial Gondar says, it is another weapon, a mechanism of action that causes difficulty for others to understand who uses it. Among us, the ability and skill to be «retranqueiro» arouses admiration. Among outsiders, perplexity and distrust. It is therefore a distinctive sign of our people.

Finally, perhaps one of the most defining traits of our culture is the presence of an alternative logic to binary logic, a logic characterized by seeing reality as a whole rather than as a conglomerate of heterogeneous elements with superficial relationships between them. In this regard, the following observation by anthropologist Carmelo Lisón Tolosana is very illustrative:

«The culture of belief is at the same time the culture of doubt. Believing and doubting […] are notcontradictory concepts but rather contrary ones that mutually and necessarily imply each other; they coexist in difference and are interwoven in dialectical relationships (witch- curer-doctor-saint), just as God and the devil are linked by a common functional semantic thread besides maintaining each their own unique meaning. The saturation of belief gives rise toand nourishes doubt, especially in matters of ritual health so fragile and uncertain, in issues of visions, apparitions, marvels, and transcendental problems — as is the case with God and the devil. The radicality of doubt is not only culturally habitual but also

advantageous and mandatory, as folklore proves in the case of the devil, an example that in its indeterminacy of reality even distorts the categorizations —God=good, Satan=bad— meticulously created and softens its own glaring contradictions because everyone is a little good and a little bad. Everything is relative.

«In conclusion, I make my own the words of historian Ramón Villares when he says that a resident of present-day Galicia can define themselves, with the same conviction as dozens of generations of ancestors, as Galician. They can recognize themselves in elemental but deeply internalized habits from a civilizational point of view, such as in their relationship with nature, eating habits, way of celebrating festivals, and possession of their own language.

8. LANGUAGE

Language is the tool we use to culture ourselves; it is the vehicle through which culture is transmitted and reflects the worldview of a people. The fact of sharing the same language — with its dialectal variants — is a fundamental constructive fact of the culture shared by a community, as human language is a constitutive factor of the social group’s identity, it produces internal cohesion, allows for the preservation of knowledge from the past, enables abstract thought, and helps understand the social structure and situation of the group. Language, as wellexplained by White, is the most representative example of our symbolic capacity, it is the essential basis for the development of culture. Language reflects the culture of a people: a largepart of cultural behavior, especially the learning of cultural systems, takes place through language. Sometimes, language is considered as a model of culture. This approach takes language as an observable form of behavior that reveals the structure of cognitive categories such as kinship, chromatic, or ethnobotanical categories that are hardly discoverable by other techniques. For example, in the field of kinship in the Galician language, we distinguish between»curmáns» (children of our uncles) and «primos» (children of our cousins, cousins of our parents, or children of our parents’ cousins). In Spanish, on the other hand, there is only one term to refer to all these parental categories: «primos,» and it is necessary to apply a qualifier (first cousin or second cousin) to distinguish the degree of kinship.

With anthropologist Franz Boas, the idea was born that language structures the knowledge and much of the unconscious behavior of a culture, but it was Edward Sapir and Benjamin Lee Whorf who explicitly formulated, between the 1920s and 1930s, the so-called Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, which assumes that the grammatical and semantic categories obligatory in a language

can structure the speaker’s thought in models or habitual patterns that organize it and thus influence behavior. That is, the theory of linguistic relativity (S-W hypothesis) says that the perception of reality varies with the speaker’s language. Therefore, peoples with different languages see reality differently and vice versa. And this fact is something extremely important when it comes to giving languages the value they really have. I will give an example to understand what we have just said: according to research in her thesis by Elvira Fidalgo, professor of Romance Philology at the University of Santiago, Galicians have 70 terms to referto rain, a meteorological element with which we are accustomed to living, while other languageshave only a couple of terms. Galicians, therefore, see many different realities related to rain when other peoples only see one or a few. The fact that Galicians possess their own languageis indicative that we share the same worldview and, by extension, as language reflects culture, we also share the same culture from the point of view of cognitive and symbolic structures. Therefore, without Galician, there would be no Galicians nor what we understand today as Galician culture, as it is transmitted, learned, and nourished in the language and, as Sapir explained, that own language conditions, whether we want it or not, our thought, our behaviors, and, ultimately, our being in the world, our culture.

Despite what has been said, and although there have always been elements that shape our distinctive and identity-constituting fact, as Clifford Geertz said (The Interpretation of Cultures, 1983), culture and identity flow, so we must abandon the idea of culture as an organic and enduring whole with values shared by all its members. Moreover, with globalization, we mustnot lose sight of the observations made by Renato Rosaldo in his work Culture and Truth: The Remaking of Social Analysis (1993) when he says that «we all inhabit the interdependent world of the late twentieth century marked by loans that cross porous national and cultural boundaries saturated with inequality, power, and domination,» and Galician culture and its identity are not immune to

these global phenomena. As anthropologist Lévi-Strauss said, «all cultures are the result of a mixture of blends and loans that have been occurring since the beginning of time, albeit at different rhythms.»

Obradoiro no Instituto Cervantes en Londres

Eduardo de Martís Fotógrafo e representante do Proxecto Galicia Latente.

OBRADOIRO NO INSTITUTO CERVANTES DO 28 DE SETEMBRO DE 2024 EN LONDRES

O presente artigo forma parte dos obradoiros que vimos realizando dende o proxecto Galicia latente. Trátase dunha iniciativa para a valorización da identidade cultural galega contemporánea.